What is a Family Crest?

If you possess any Japanese family heirlooms, there is a chance one of those objects is adorned with your family crest. Particularly in the decades leading up to World War II, family crests were embroidered on formal attire like kimono, haori, and personal accessories, as well as on important possessions like family Buddhist altars.

However, after the war, Japan became increasingly westernized. Family crests were suddenly considered traditional and a bit outdated, and so they were used less in everyday life. Nowadays, the most common place to see a family crest is on a gravestone. And even then, fewer people have traditional graves these days; as a result, there are a considerable number of people who not only don’t have anything with their family crest on it, but who don’t even know what their crest is.

A family crest is a symbol that represents a family line which has been passed down from generation to generation, something akin to a family logo. However, it is important to remember that it is not purely tied to a surname, but to your own unique family line; for example, not everyone with the last name ‘Tanaka’ has the same family crest. Even those with the same surname have different crests based on their place of origin, lineage, traditional business, etc., resulting in a wide variety of different crests. As a result, the family crest serves as an inherently unique symbol that allows people to more closely connect with their roots.

The Origins of Family Crests

There are said to be more than 6,000 different types of generally similar family crests, and if you distinguish between their details, there are more than 20,000 unique crests. To understand the origins of these family crests, we need to look more closely at the culture that they were formed in.

The Origin of Noble Family Crests

There are three popular theories regarding the origin of the family crests used by noble families. Some would even argue that they may all be true, as individual families developed their own symbols independently of each other.

The first theory comes from the Heian period (794-1185), an era known for the cultural developments of the imperial court. For nobles of the time, the ability to travel in ox-drawn carts was a sign of prestige, leading to these carts being present at court in large numbers. Nobles began to mark their carts with crests as a way to show off their prestige and mark their belongings, even seeking to outdo each other with increasingly elegant designs. These cart crests are said to be one of the potential origins of the family crest.

A more simple theory argues that crests were influenced by the clothing of the nobility. When they found cloth patterns they liked, nobles would take that symbol and implement it as their own official crest.

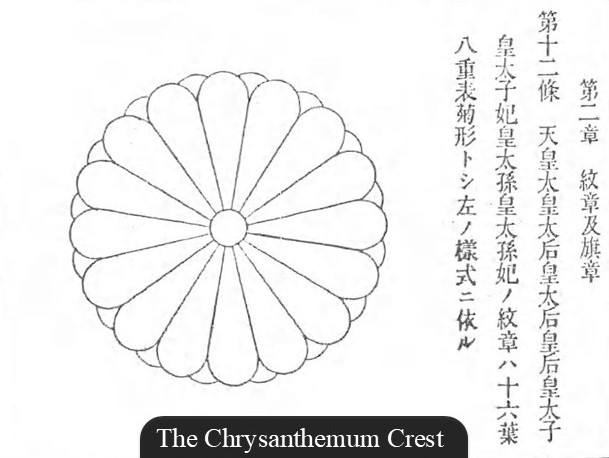

In contrast to this more practical take, the third theory states that family crests were chosen due to some special, personal meaning. For example, if a noble loved plum blossoms, that family may create a crest centered around the symbol of a plum blossom to memorialize that feeling. This can be seen in the widely recognized ‘chrysanthemum crest’ of the imperial family, which is said to have originated from Emperor Gotoba in the 12th century. As he had a particular fondness for chrysanthemum flowers, their image adorned much of the furniture of the imperial household and was eventually adopted as the symbol of the emperor himself.

The family crests of noble families thus have multiple different potential origins, with no one theory being regarded as more true than the others. But in all of these cases, they were created not to fill a need, but instead arose as an extension of decoration. And despite their various motivations, what they all have in common is that designs using patterns or motifs connected to the family later became not just decorative, but developed into official, recognized symbols of a family’s authority.

As these family crests began to be recognized by other people, they became a convenient sign for both showing one’s authority and identifying a family’s belongings. As a result, these family crests began to be passed down between generations in order to retain that symbolic power, sharing it with the successive members of a noble’s lineage. As a result, family crests as we understand them today were implemented around the end of the Heian period, in the 12th century. However, this only applies to the family crests of the nobility; the family crests of samurai are a different matter.

The Origin of Samurai Family Crests

Even though family crests had been fully established for nobles, they did not immediately spread to the samurai warrior class, and when they did, it was for a more practical purpose. Unlike the nobility, samurai made their living through fighting, and so family crests spread in relation to their usefulness in war.

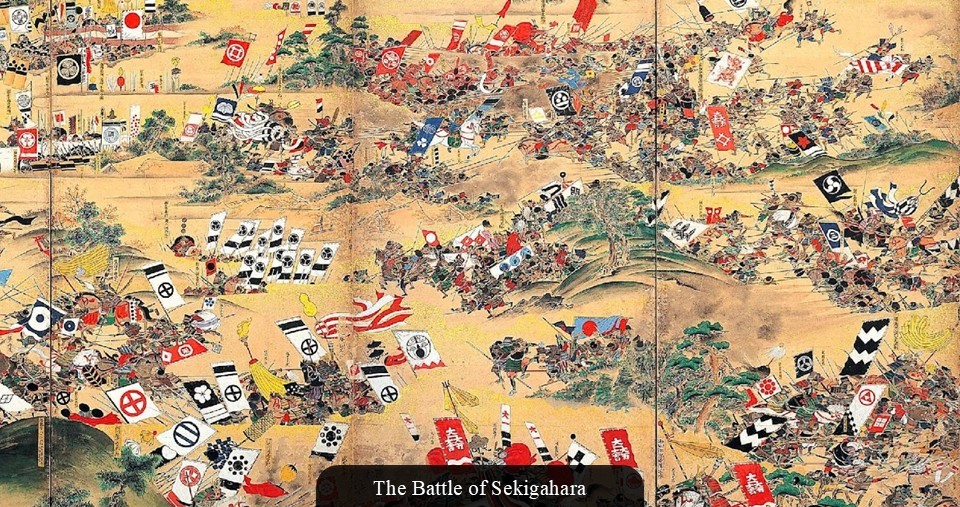

In battle, it was necessary to distinguish friend from foe. During the Genpei War in the 1180s, this was done with colored flags; one side, the Minamoto, used white flags, while the other, the Taira, used red flags. But while this system allowed them to quickly grasp the basic distinction between sides, it was still difficult to know where individual commanders and their troops would be. As a solution to that problem, by the 1500s, samurai warlords began to mark their flags and tents with unique symbols, a practice which quickly spread. Just as with the nobility, there are three generally recognized origins for samurai family crests.

The first are hatasashimono (旗指物), banners that warriors would carry into battle. These symbols spread, and were soon painted on helmets and armor, an effective method of allowing a reputable warrior to make their presence known. When these symbols were passed down to the next generation, they became family crests.

A second, very similar origin comes from the large curtains that surrounded battlefield encampments. By marking these curtains with a leader’s unique symbol, it became relatively easy to understand who was in charge. As the camp was where tactics were decided, these curtains were seen as symbolic of the samurai class, a level of importance that perhaps influenced these symbols’ adoption as family crests.

The third theory overlaps with the theories about nobles’ crests, positing that some samurai crests were based on clothing patterns. If a warrior’s armor was already decorated with a particular cloth pattern, then it could be repurposed as a symbol of that samurai individually, later fully developing into a family crest.

Regardless of their specific origin, these family crests, which served as markers in the heat of battle, were widely recognized as valuable. As a result, bestowal of a crest upon a distinguished retainer was a noteworthy reward, a sign of just how much meaning these symbols carried. These crests symbolized military unity and represented a samurai’s status and loyalties, a weighty meaning that only increased as they were used by subsequent generations.

Differences Between the Crests of Nobles and Samurai

Despite their shared characteristics, there were still key differences in the crests used by samurai when compared to those used by the nobility.

At the most basic level, these crests were visually different. Nobles preferred ornate designs as a symbol of their authority, while samurai preferred practical, simple designs that were easy to understand in battle.

There were also differences in their adoption. While family crests originally represented family names, being roughly tied to a surname rather than a single lineage, by the Sengoku period of the 15th and 16th centuries, it became common for clans that shared the same family crest to fight each other. As a result, these samurai began to alter their crests for practicality, naturally increasing the types of samurai crests. Due to this growth, there were more varied crests for samurai than for noble families, whose ranks were fixed.

Though the nobility had developed crests earlier, they did not have any significant meaning beyond showing authority and marking property. When compared to the samurai crests, which were needed in battle, there is a clear distinction between the two both in the speed of their spread and the necessity of their development.

Restrictions on Family Crests

As the unrest of the Sengoku period began to fade, official restrictions on family crests were put in place. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of Japan’s Three Unifiers, issued a ban on the use of the chrysanthemum and paulownia crests in 1591. The chrysanthemum crest had served as a symbol of the imperial family for centuries, and the paulownia crest was a prestigious alternative that was often used in an official capacity. Recognizing the increasing importance of crests and the authority that they carried, Hideyoshi limited their use to preserve that symbolism. As he also sought to solidify a class system, he ruled that commoners were not allowed to possess family crests of their own, creating clear distinctions between them, the samurai, and the nobility.

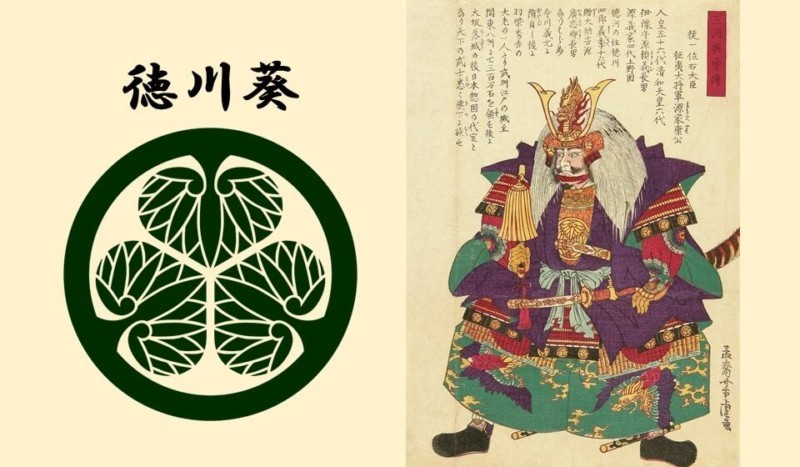

However, when the Tokugawa-ruled Edo period began in 1603, the atmosphere surrounding crests changed. As an era of peace, samurai family crests were not needed in battle, instead becoming symbols of authority much like those of the nobility. Restrictions on crests for commoners were also relaxed, and family crests began to spread to commoners and townspeople.

The Flourishing of Family Crests in Edo

When Tokugawa Ieyasu took control of Japan as shogun, he declined to use the inherently prestigious paulownia crest (菊桐紋) that was offered to him by the emperor. Instead, he moved to monopolize a crest containing a portrayal of hollyhock, known as the Aoi Crest (葵紋) in Japan. While the Tokugawa family’s unique use of this crest was not enforced in the early years of the shogunate, a strict ban would be issued more than 100 years later, due to the crest’s unauthorized use on products.

Upper Class Crests

With the aoi crest cemented as the symbol of the Tokugawa shogunate, it came to have an authority far surpassing that of the crests of the imperial family. Following this example, local daimyo, Japan’s feudal lords, began to use family crests as status symbols of their own, printing their crests on everything from furniture to clothing.

The use of these crests was also practical, with a readily visible example in the system of alternate attendance. Every year, the daimyo were required to move their household between Edo and their own territory, switching their primary residence each year. This led to regular, lavish processions which were decorated with the family crest, making it simple to identify the lord at a glance. As etiquette would differ depending on the lord’s rank, it allowed for passersby to quickly understand exactly where they stood in the social hierarchy. This was particularly important in the event that two such processions would meet each other on the road, leading to the head of the train often being someone who was familiar with the crests of each daimyo.

For when these processions reached Edo, the shogunate’s guard included officials who were properly versed in each daimyo’s family crest, as it made them more capable in their official duties. The townspeople of Edo, particularly those who worked in and near the shogun’s castle, were also often informed about these high-status crests; it was necessary to identify the station of a samurai at a glance in order to respond accordingly, as failure to do so would be extremely troublesome. As a result, books were regularly published with compilations of the various crests of the daimyo, a practice that continued until the Meiji period.

Though literacy in Edo Japan was relatively high, it was not universal. It made sense then to use family crests as signage, as they were a symbol of authority that could be identified by the general populace.

Crests of the Common People

The use of family crests spread to the common people as well, and for good reason. The Tokugawa shogunate strictly enforced a class system, with samurai and their lords standing above the common populace; farmers, artisans, and merchants. This stratification was visibly enforced with restrictions on carrying swords and having surnames, with these privileges reserved for the upper class.

But while a surname was a symbol of status, a family crest was not, with their use becoming increasingly widespread. Adopting a crest also became fashionable, as commoners sought to emulate famous actors and the popularized samurai ideal, in some cases even copying the crests of those they admired. The use of family crests became so widespread that some individuals made a living as professional crest designers, and were often in high demand.

These crests became particularly important to merchants and craftsmen, as they could serve as a symbol of their brand, signifying quality and reliability. In some cases, the shogunate recognized particularly outstanding works by bestowing a seal upon the artisan, lending even more prestige to that individual’s work. With craftsmen taking pride in their work crests, many began to use those same symbols as their own family crest. Even today, there are some crests that have been passed down at long-established stores that have been in business since the Edo period.

Similarly, merchants also relied on the strength of their reputation. They had both their store’s name and a crest tied to their brand. With that crest becoming an important symbol, often displayed on the curtains at the entrance to a shop, merchants would take that same symbol as their own family crest, tying the reputation of their family to that of their brand.

Even among farmers, who were not necessarily customer-oriented, there was a spread in the use of family crests. Large, wealthy families in particular began to use crests as a way to show their family identity, a way to set themselves apart from their peers. Still, farmers’ crests had a less specific purpose than those of artisans and merchants, instead being suffused with a stronger decorative meaning.

While commoners may have initially used crests as a fashion or business statement, they eventually followed the example of the samurai and passed these symbols down to the next generation as family crests. Commoners sharing a given name had previously been identified by their hometown or occupation, since they were prohibited from using surnames. Crests provided an alternative, serving as a visual way to confirm a person’s identity, and helping to overcome some of the inconveniences of having a single name.

The Meiji Era and Beyond

Japan’s political system was drastically overhauled in 1868 with the start of the Meiji Restoration. With the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, the class-based societal system was abolished. Commoners were now not only allowed to have surnames, but required to choose one by 1875 as part of modernizing population registers. This led to another wave of popularity in creating family crests associated with these newly chosen names; as a result, every Japanese now had a surname, and most had their own crest as well. But while surnames were recorded and registered, crests have never been managed by an official system, making them more in danger of dying out and being forgotten.

In a reaffirmation of the symbolic power of crests, the chrysanthemum crest, representative of the imperial household, was officially reserved for the emperor. While the crest’s authority had declined under the shogunate, this new development restored the symbol’s power, even as the authority of the Tokugawa crest faded. Likewise, the associated paulownia crest, which had long been regarded as prestigious for its relation to the emperor, is today the crest of the Japanese government, with a variant serving as the symbol of the Ministry of Justice.

Family Crests Revealing Family Origins

When looking back at history, family crests essentially serve as a mirror reflecting the era in which they were created. In researching your own Japanese ancestry, focusing on family crests that have been passed down for centuries may help you find insights regarding your Edo-era family. By investigating the details of your family crest, you may find commonalities with the daimyo of the region in which your family lived, or learn about your ancestors’ occupations. In this respect, the design of your family’s crest serves as a time capsule to the past, holding secrets that can help you learn more about your own history.

Request a Free Consultation